The Music of the Spheres is an ancient philosophical concept that envisions the cosmos as a vast, geometrical system of harmonic proportions, where celestial bodies move according to mathematical principles and generate an inaudible series of tones that together create a sort of “divine symphony”.

Allegedly originating with Pythagoras, who proposed that the movements of the planets followed harmonic ratios akin to musical intervals, the idea was later expanded by Plato, who described the universe as being structured through a cosmic order of sound and number.

The Roman philosopher and polymath Boethius further developed the concept in the Middle Ages, distinguishing between three types of music: musica mundana (the music of the universe), musica humana (the harmony of the human soul and body), and musica instrumentalis (audible music).

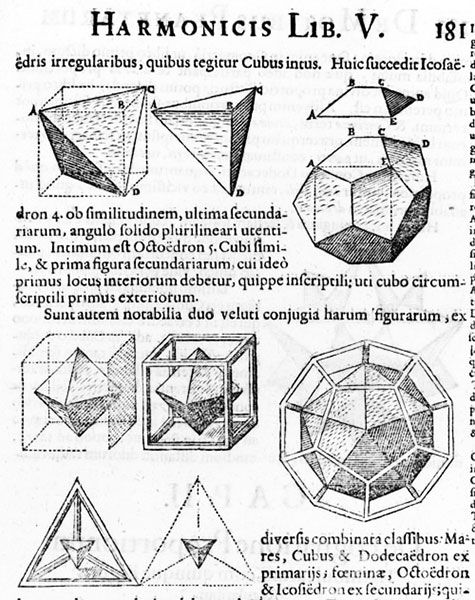

During the Renaissance, Johannes Kepler sought to provide a scientific foundation for this theory in his work Harmonices Mundi, suggesting that planetary orbits followed proportions based on the Platonic solids.

Though the Music of the Spheres cannot be physically heard, it symbolises the fundamental unity of the cosmos, influencing spiritual thought, artistic inspiration, and the pursuit of higher wisdom throughout history.

As a poetic concept, the Music of the Spheres is as inspirational as it gets, especially amongst those who are drawn to the power of sound and music and their therapeutic effects.

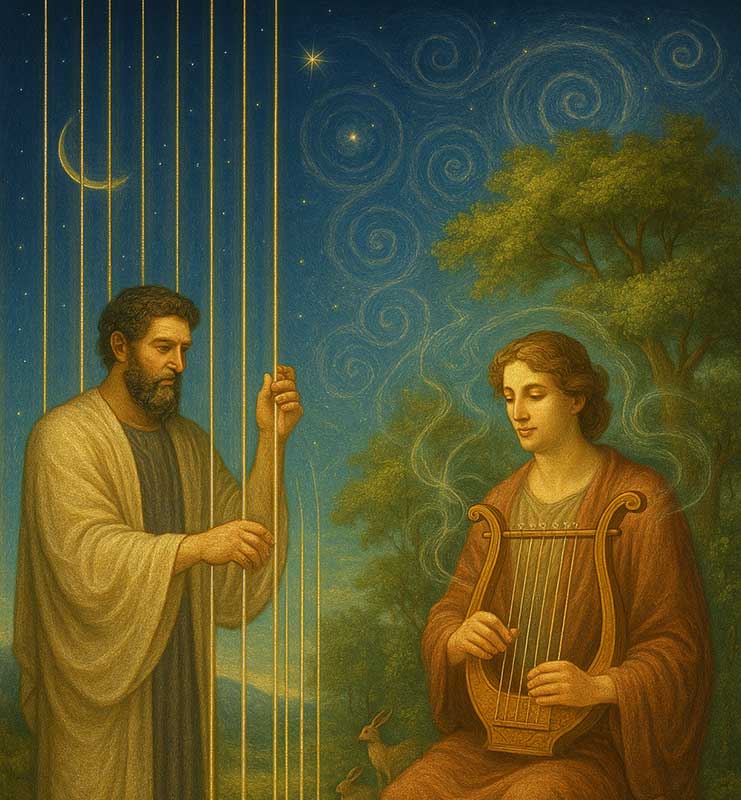

However, for a truly holistic approach to the therapeutic use of sound, one has to reconcile the concept of the Music of the Sphere (and every musical heritage stemming from the Pythagorean philosophy) with the more earthly and earthy footprints of the Orphic tradition.

That Pythagoras is commonly accepted as a historical figure, while Orpheus is part of ancient Greek mythology, hinders the possibility of recognising both characters as representative of two fundamental qualities of the human psyche. If we considered both characters as mythological, the key to such interpretation would be more accessible. And, in fact, it is not a given that Pythagoras really existed.

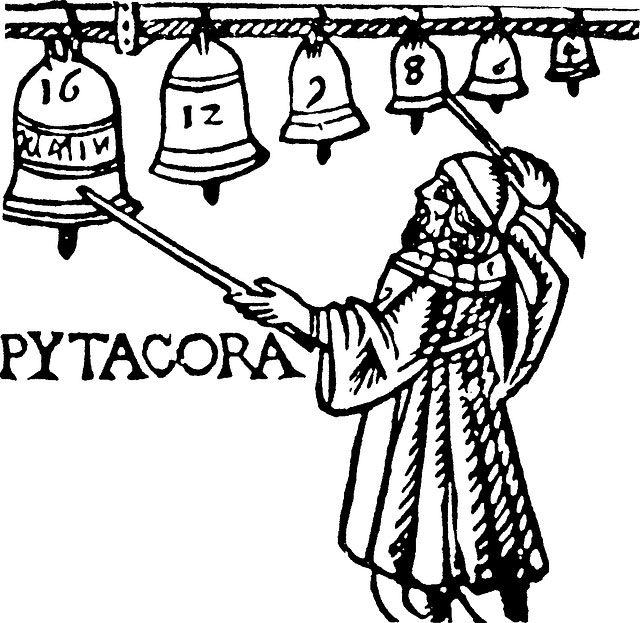

Known amongst other things for his mathematical approach to music, Pythagoras believed that all things in the universe could be explained and understood through numbers and ratios. He allegedly discovered the mathematical relationships between musical notes and the lengths of vibrating strings, which laid the foundation for Western modern music theory. Such musical knowledge was not new to other cultures and civilisations and the same goes for his well-known theorem on the properties of triangles. What seems to be unique to the Pythagorean philosophy is an untamed faith in numbers and ratios. The Pythagoreans placed great importance on the purity and simplicity of musical intervals, viewing them as reflections of the divine order of the cosmos.

In contrast, Orpheus was a legendary musician and poet who was revered for his ability to charm even the wildest of beasts with his music (interestingly, an ability also attributed to Pythagoras, who was said to be able to change people’s emotional and mental states with music). He is said to have descended into the underworld to retrieve his beloved Eurydice, using the power of his music to sway Hades himself. Orpheus represents the belief that music has the power to transcend the material world and connect with the divine.

They both represent the transformative power of sound and music.

Taken as two sides of the same coin, they represent the dual nature of music, which can be both a scientific study of harmonious vibrations and a mystical art form that transcends human understanding.

Isn’t it interesting that Pythagoras, being associated with mathematics and philosophy is accepted as a historical figure while Orpheus, who is more of a musician/magician with abilities similar to those of a real shaman, can only be accepted as a myth?

Pythagoras

The life story of Pythagoras, or rather, the legend surrounding him, comes from numerous works of ancient writers, including esteemed figures like Herodotus and Aristotle. The challenge, however, is that these biographers did not rely on firsthand accounts from Pythagoras’ contemporaries, as no such records existed. Instead, later authors such as Diogenes Laertius and Iamblichus documented information that had been passed down orally as part of the philosophical tradition.

The earliest written material about him that is accepted as genuine comprises six fragments of text dated a century after his death and they are all not original but rather quoted by authors who are supposed to have read the originals.

During the centuries following his death, a lot has been written about Pythagoras. The material varies from attempts at biographies, descriptions of his many virtues, recounts of miraculous events, as well as derogatory and scornful texts.

Pythagoras was born in Samos, Greece, and moved to Crotone, Italy, around 530 B.C.

In Crotone, the Pythagoreans gained considerable political influence, strengthening the city’s power. However, this eventually led to the persecution of the school’s members. After Pythagoras’ death, his followers fled, spreading his teachings across the ancient world. Over time, many of the school’s achievements were attributed directly to Pythagoras himself, making it difficult to determine the original foundations of his doctrine.

One can think of the life of Pythagoras along the same lines as that of Jesus: everything we know about him has been written long after his death, edited, translated, exalted, and confuted, leaving us to decide what to believe. Whatever historical truth was there at the beginning, has been coated with mythological tales that are functional to the message that is to be communicated.

Pythagorean knowledge or philosophy is really a compound of work by various later authors who referred to Pythagoras as a sort of symbol of Sophia. In fact, in ancient times, relating one’s ideas to revered characters of the past was a way of validating them and contributing to a lineage of wisdom. It is important to understand this point because today we often witness the opposite when people don’t give full credit to their sources. So, attributing one’s philosophical insights to Pythagoras has been a common practice throughout the centuries, making it very difficult to separate the original information from everything that has been built upon that.

Pythagoreanism, as we know it today, is the sum of the work of Plato, Aristotle, Porphyry, Heraclitus, and Iamblicus to name but a few in ancient times, Boethius in the Middle Ages and Kepler in the Renaissance.

The Pythagoreans held the first four numbers (tetraktys) in the highest consideration. From a musical point of view, this is interesting because they are used to define the ratios of the most universally recurring musical intervals: the octave (2:1), the fourth (4:3) and the fifth (3:2).

However, this faith in the neat order that arises from simple ratios must have been seriously put to the test by the insidious “Pythagorean comma”, the thorn in the side of simple harmony.

The Pythagorean comma

The Pythagorean comma is a small tuning gap that happens when you tune notes using pure perfect fifths. If you stack twelve perfect fifths in a row, you expect to end up on the same note you started with (seven octaves higher)—but you don’t. The last note is slightly higher than expected by a tiny amount (about 1/9 of a whole tone). Considering that, in Pythagorean tuning, one obtains all notes of a scale by a series of successive perfect fifths, the comma poses a very inconvenient problem.

(If you wish to learn more about tuning systems, you can read this article.)

This illustrates how an ideal created by pure intellectual speculation can be proven incorrect once it lands in physical reality.

It wouldn’t be surprising if this was the seed (or at least one of the seeds) of a certain bizarre way of thinking that considers nature and the physical world to be somewhat faulty, at least in the Western world where the Pythagorean philosophy was quite influential. Such ideas have been entertained by various spiritual traditions and one can’t help but to wonder if they stem from the intellectual frustration instigated by Nature’s unwillingness to be nice and tidy.

The slight discrepancy between the golden ratio and the Fibonacci sequence is another example of this, but that’s another story.

Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) is another character whom we learn about in school for his laws of planetary motion. What we don’t learn in school is that he realised these ideas (still valid today) while trying to demonstrate that the solar system is arranged musically by harmonic principles. He devoted his life and intellect to understanding and decoding these principles from a deeply religious vocation to understand and honour God’s intelligent design.

The implications of Kepler’s discoveries are vast. Kepler’s calculations of the ratios between the orbits of the planets were extremely accurate. French philosopher and mathematician Francis Warrain in the first half of the 20th century verified all of Kepler’s values and added the calculations for Uranus, Neptune and Pluto (unknown at Kepler’s time).

He measured the angles that each planet forms in 24 hours as seen from the Sun while moving at the closest (perihelion) and at the farthest (aphelion) distance from the Sun. He then converted the ratios resulting between the two positions into musical intervals, rendered in the key of C, although it could have been any other key.

Remarkably, of the 76 resulting intervals, 72 belong to the major scale, with 58 of them falling on the notes C, E and G (i.e. the major chord in the key of C).

Although Kepler first started constructing his harmonic model of the solar system based on circles and spheres, within which he would place the five platonic solids, he later found this to be a fallacious model and years after he realised that the orbits of the planets are not perfect circles, but rather ellipses.

In a way, he transcended the human mind’s need for perfect, rational numbers and simple orders. He accepted that the physical reality expresses itself in complexity. That was the key to his findings. The universe is not determined by mathematical principles, or at least, not by extremely simple ones . Rather than approaching his research from a mathematical point of view, he investigated harmony as a physical occurrence. What we can intuit from his discoveries is that perfect ratios do not produce harmony, they result from the physical reality of harmonic consonance. It is a subtlety, yes, but pivotal in the understanding of nature.

Total trust in a completely rational universe is a manifestation of the rational thought typical of Pythagorean tradition. A balanced observation based on complementing rational and intuitive (Pythagorean and Orphic, one could say) allows us to see that the unfolding of creative processes does not follow only one direction (from spirit to matter, so to speak) but rather it develops both ways.

The oscillations and “imperfections” that will always defy the need for absolute values are, with the harmony of the spheres, very similar to the constant minute adjustment of tuning that musicians and singers do while performing in ensembles. If you listen to a choir or an orchestra, you will never hear the sum of several instruments and voices producing consistent and perfect pitches. What you hear is the constant work of attunement to each other in order to keep the shape of harmony together.

We can imagine the solar system the same way, an ensemble of planets creating a constant harmony based on their constant adjustments of velocities.

The dance of life is the dance of the three gunas of the ancient Samkhya philosophy. Sattva, Rajas and Tamas are the three properties of the universe. As long as they are in perfect balance, the universe only exists in its potential state. As soon as one of the three goes out of balance, the dance between the three begins in order to gain balance again, a universe is born. The universe can be seen as the movement of these three principles (similar to the positive, negative and neutral cosmic principles, or holy trinity) in their attempt to regain balance and stillness.

However, we fail to appreciate the complexity of life when we create philosophies and religions that identify the stillness of Pure Existence with perfection and the birth of life as a search for that balance as imperfect.

With all this in mind, I had some fun creating a new “ancient” mythological tale, where Pythagoras and Orpheus are both mythical characters that represent two ways we have to observe reality.

The Harmony of Two Souls: Pythagoras and Orpheus

A long time ago, in the ancient realm of Harmonia two brothers were born under the same celestial sign and their destinies were intertwined with the very fabric of sound. One was Pythagoras, whose mind sought order in the universe, believing that all things could be measured and mastered through numbers. The other was Orpheus, whose heart beat in rhythm with the unseen forces of the world, understanding that true harmony could never be fully captured, only felt.

As children, they both marvelled at the power of sound. Pythagoras, ever curious, stretched strings over wood and measured the tones they made. He noticed that if he glided his finger over a string with a light touch, there would be certain points where harmonic sounds would be produced. He devised that by dividing the string into precise lengths based on those points, he could create what he considered perfect harmonies. “Behold!” he declared, “Music is but numbers made audible! The universe itself must be built upon such perfect ratios.”

Orpheus was not overly impressed by this. He walked among the forests, listening to the rustling of leaves, the call of the birds, and the murmur of the rivers. “Brother,” he said, “these sounds follow no perfect measure, yet they move the soul. It seems to me that Nature sings with a wisdom beyond counting.”

Pythagoras believed that the heavens themselves must sing in perfect mathematical intervals, a grand cosmic symphony dictated by reason. Orpheus, however, closed his eyes and listened. He heard something earthy, a music not bound by rigid structures, but by the flow of life itself.

Years went by.

One starlit evening, as both brothers gazed upward, the goddess Melodia descended in a burst of shimmering light. “Harmonia suffers from discord,” she declared. “To mend the rift, your wisdom is needed, a healing through sound is necessary. Your instruments, your gifts, must be used to express pure harmony. Only then will the world be whole again.”

Determined to prove his mastery, Pythagoras set out to create an instrument so perfect that it would mirror the very order of the cosmos. He built a magnificent set of celestial strings, each tuned to his sacred ratios. When he played, the sound was so pure and precise that it seemed to pierce through the very fabric of reality.

Orpheus, in turn, picked up his lyre, but instead of following strict measures, he let his fingers wander. His music was wild yet beautiful, unpredictable yet full of meaning. The winds changed, the trees swayed, and even the stars seemed to listen.

Pythagoras bristled with certainty. “The universe is a grand equation, and my perfect strings can prove it!” he proclaimed.

Orpheus replied softly, strumming a gentle chord on his lyre, “Yet without the heart’s intuition, even the purest note is lifeless. The beauty of music is found in its ebb and flow, not just its precision.”

Pythagoras grew frustrated. “You ignore the laws of perfection! Music must be controlled, structured. Only then can it reflect the divine order.”

Orpheus shook his head. “You see only what can be counted, but true music is alive. It bends, breathes, and transforms. The universe does not obey numbers, it sings them into being.”

And so, the two brothers, instead of working together, drifted apart. By that time, Pythagoras had become a great teacher, and founded a school where disciples learned the sacred numerical laws of harmony. Orpheus wandered the earth, touching hearts with music that could not be written down, only experienced.

The Journey Toward Unity

Still mindful of the goddess’ message, each brother embarked on a journey. They wandered through enchanted forests, where the spirit of nature whispered its secrets, and crossed crystalline rivers that carried the echoes of ancient songs. One night, while resting in distant parts of the land, they both had the same dream where they heard a voice saying: “Seek the truth in the space between perfection and imperfection.”

Their quests lead them to climb to the top of the Singing Mountain almost at the same time. The first to arrive was Pythagoras, who started setting up his majestic cosmic strings. Having already discovered the harmonic power of the perfect fifth, he devised they could be arranged in a circle and put into perpetual motion, thus creating an everlasting vibration of pure harmony. However, once his creation started spinning, what should have been perpetual motion was interrupted because the last of twelve fifths did not start the cycle again. It simply stopped. Upon examining his creation, Pythagoras was shocked to find that the last of twelve fifths did not coincide with the first note. It should have been the same note five octaves higher, but it wasn’t!

That’s when Orpheus also arrived at the top of the mountain. Meanwhile, he had found something even greater than song: silence, the space where all music is born and to which all sound must return. He felt that the space of silence was where he wanted to spend most of his time but he also realised that in total silence, he wouldn’t be following the Goddess’ request for a harmonic solution to the current state, which needed to be expressed through sound.

Stepping forward, he said: “That gap is not a flaw, but the place where life’s unspoken beauty resides,” he said. With that, he began to play. His lyre sang of forests and rivers, of joy and sorrow, a melody that wove the dissonant note into a tapestry of sound. The rigid structure of Pythagoras’s tones blended with the flowing warmth of Orpheus’s melody, transforming the discord into a profound, living harmony.

The Revelation

Pythagoras exclaimed his realisation: “It’s not a circle, it’s a spiral! An everlasting spiral of fifths!”.

In that transcendent moment, the brothers realised that neither pure reason nor unbridled intuition held all the answers. The universe was too vast, too wondrous, to be explained by numbers alone. Pythagoras discovered the harmony of the pure fifths and Orpheus could see that their not lining up as a circle was not a fault, but rather the key.

The true essence of music, and of life, lay in the interplay between the two. Structure without life is empty; intuition without form is fleeting. Only by embracing both could true harmony be found. Only in their union could the world’s hidden laws be revealed.

And so, their music, though different, became part of the same great song, the song of the cosmos, where reason and magic dance together in endless, unfolding sound.

The goddess Melodia, smiling upon their reconciliation, blessed Harmonia. From that day forward, the myth of Pythagoras and Orpheus was passed down as a timeless reminder: true harmony is achieved not by forcing nature to fit a mould, but by embracing both its logic and its mystery.

Check our other articles

Sound Therapy and Neurodivergence

The Resonant Power of Sound Healing for Neurodivergent Individuals In a world filled with sensory stimuli, neurodivergent individuals, such as those with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), often experience heightened...

Sound, Mass and Magnetic Fields

Sound, as we commonly understand it, is just a vibration that travels through air, water, or solid materials. It's what we hear when air molecules move back and forth, creating pressure waves. But in recent years, scientists have discovered that sound is more than...

How We Hear: Exploring the Models of Auditory Perception

The process of hearing is a marvel of biological engineering, involving intricate mechanisms that convert sound waves into electrical signals interpreted by the brain. Over the years, scientists have proposed various models to explain how hearing works, each shedding...